This week I had my “Food and Power” students do an interesting experiment: to keep a food diary of everything they eat (and drink) for 7 days. I asked them to take photos, email me two (one pic of their most representative food, and a second of their most special food that week), and on Thursday for our class I made a slideshow from the photos for discussion. I opened with Anthelme Brillat-Savarin’s famous statement, “Dis-moi ce que tu manges, je te dirai ce que tu es” (transl: tell me what you eat and I will tell you who you are). And I asked them: What does the food you ate this week tell you about yourself?

This week the course topic was “Gluttony”, and more specifically nutritionism and the so-called obesity epidemic. So to make their assignment more complicated, I ask them to calculate their daily calorie intake, which, if you’ve never tried it, you might not know is very difficult to do. Indeed, my secret goal of this assignment was to show them how difficult it is to keep precise track of every calorie you eat. In discussion this challenge came up quickly. One student laughed and said all her pictures were of half eaten food, because she only remembered to take them after the fact. Several students said it was hard to remember to include liquid calories (fruit juices, sodas, etc.). One of my students said coffee was her most representative food, an interesting claim since coffee is a beverage, which she defended by pointing out that a cup of black coffee has an average of 20 calories. And we all agreed that it will be difficult calculating the calories for many sauces and dips (e.g. mustard, BBQ sauce). We discussed these different types of “invisible calories”, and what Brian Wansink calls “Mindless Eating“, the ways we eat without noticing that we are eating that sometimes contribute to our eating too much.

This week the course topic was “Gluttony”, and more specifically nutritionism and the so-called obesity epidemic. So to make their assignment more complicated, I ask them to calculate their daily calorie intake, which, if you’ve never tried it, you might not know is very difficult to do. Indeed, my secret goal of this assignment was to show them how difficult it is to keep precise track of every calorie you eat. In discussion this challenge came up quickly. One student laughed and said all her pictures were of half eaten food, because she only remembered to take them after the fact. Several students said it was hard to remember to include liquid calories (fruit juices, sodas, etc.). One of my students said coffee was her most representative food, an interesting claim since coffee is a beverage, which she defended by pointing out that a cup of black coffee has an average of 20 calories. And we all agreed that it will be difficult calculating the calories for many sauces and dips (e.g. mustard, BBQ sauce). We discussed these different types of “invisible calories”, and what Brian Wansink calls “Mindless Eating“, the ways we eat without noticing that we are eating that sometimes contribute to our eating too much.

I used this challenge of recording each and every food item to talk about the limits of diet epidemiology. One of the recurring themes I return to in the class discussions is: How do we know what we know about food? (It’s a question I first heard stated by Alan Brandt: how do we know what we know about… anything?) In medicine the presumed “gold standard” for knowing something is the Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Yet, some things are more amenable to this kind of study than others. Pills, for instance, are easy to do: you have an experimental group take the real drug, and a control group take the placebo, and nobody knows which is which. But imagine trying this with food. Who do you think you will fool when you give one group the low-fat food, and the other the normal one? (Surgery is another area where RCT is not an option: it has been decades since “sham surgery” was allowed as an ethical option for a control group.)

My lecture slide on the limits of knowing: I love this pyramid on the hierarchy of knowing, from the satire website The Spud.

Moreover, in studies testing some specific change within a diet, epidemiologists say it is a nightmare trying to get exact information about what exactly their participants are eating day to day. Either they rely on surveys, whose reported information is dubious. (Ask yourself, what did you eat yesterday, and see if you can give a good answer.) Or, they have participants keep a diary, and then nurses are tasked with calling them to remind them to keep the record. And invariably participants don’t, and the size of the study gets smaller and smaller. Bringing us back to my students’ challenge this week.

Of course, there are certain special people who do manage this kind of nutritionally obsessive work day to day, and we talked about them. Diabetics have to be very careful about the quantities of foods that take in, for sugars. People with food allergies or celiacs, who are in my experience those who most carefully read a food label. Pregnant women are also increasingly getting pulled into this kind of biomedical model of managing one’s diet. But these are the exceptions that prove the rule. They are unusual in that their diets are not so much framed as food choices, and therefore are not about “will power”.

Two other types of people obsessed with diet fit into what Robert Crawford so elegantly identified 35 years ago as “healthism“: athletes and vanity dieters. Indeed, last Sunday, as it happened, I ran my first marathon (the Seoul International Marathon in 4:45:29!). So when I described my representative food for the week, I introduced it as “carbs”, falling into the nutritionism trap. Why consider spaghetti carbonara to be the same as Chinese noodles with blackbean sauce when they hail from completely different cultures? (According to RunKeeper, I burned 4,000 calories during the race. I asked my students, what does this mean?) But these kinds of lifestyles demand an abnormal level of will power. (I simply refuse to live my life as a health-conscious marathoner. One time, sure, but as a constant state of being, no way!) Do we really expect ordinary mortals to track their eating in such a careful, deliberate manner? Not really. But it’s a problem for scientific eating.

My Food Dairy was completely distorted by the fact that this week I ran my first marathon, and was therefore obsessed with “carb loading”.

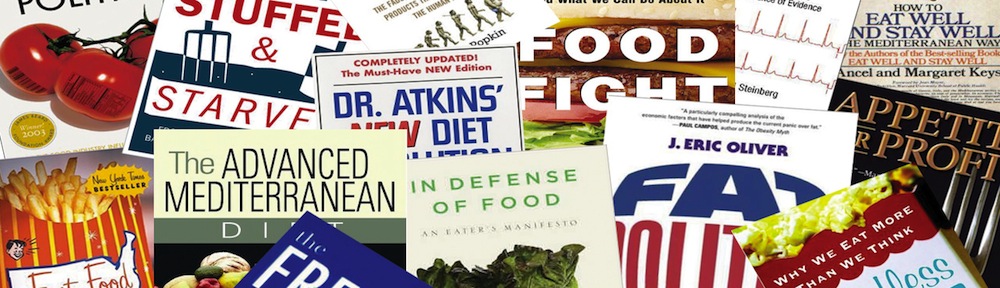

Gary Taubes, science journalist and all-around science debunker crank, wrote a New York Times article in 2002 titled: “What If It’s All Been a Big Fat Lie?“, where he basically assaulted the lipid hypothesis and argued that because there were no solid RCTs on it, it wasn’t good science. But then Taubes, and later Michael Pollan, fell into the regular trap of putting forward some other theory (evil carby diets), ignoring the fact that there wasn’t “good science” by his impossible definition for that either. Thinking about Taubes and his ever elusive Gold Standard, and how even my brilliant capable KAIST students found it difficult keeping a scientific record of what they eat, I wonder if there are certain things that are just not “knowable” scientifically. Rather than lapse into Taubes’s absolutism or some equally unproductive opposite relativism, I used this example to caution my students to approach diet science advice with care. In general, if someone tells you some diet thing is “science”, odds are they are trying to sell you something… it might be the food, or it might be their expertise (or in Taubes’s case his expert-debunking expertise), but they’re selling you something. In which case, buyer beware!

Putting aside these issues of nutrition, the food diary was also a good class experiment for other reasons. It got them to think about what and how they eat, and how everyone is a little different. Some have small snacks regularly throughout the day, others 2-3 periodic meals which punctuate their daily schedule. One of the big questions for my college students, to skip breakfast or not. And in my Korean class there was the other interesting question: Western breakfast or Korean breakfast? The class experiment had a collateral benefit: to get to know the students better, and encourage them to relax and enjoy the class. (One student said his roommate, not in the class, thought it was a neat idea and also tried it, which I will interpret to mean the project is fun to do.)

I’ve given them a take-home survey, to draw out these observations made in class discussion. It has the questions discussed above designed to get them thinking about their diet generally, and about the things they didn’t notice about it: What was your most representative (normal) food/meal? What was your most special (significant or unusual) food experience? Were there any foods you documented that you hadn’t really “noticed” before this “experiment”? (e.g. liquid calories, snacks) I wanted them to think about the differences in eating alone versus eating with people, both because we tend to eat differently (and thus digest differently), and, to anticipate a theme we are going to take up later in the course, because these social influences or constraints are often more important than the myth of the individual eater making a choice in isolation, when determining how and what we eat: What time of day do you get most of your calories? How long does your normal meal last (are you a rapid eater)? Do you eat with friends/family or alone?

Lecture slide where I get students to think about other factors, other than nutrition, that motivate us to eat a food. I also ask the students: what are other ways that we talk about food and health, without using nutrition. (E.g. organic, wholesome, what mom used to eat, seasonality, freshness…)

But I also added some questions to get them to think about the experiment itself: Did you change or modify your diet as a result of the “experiment”? How? In general, students said they didn’t change much. (A relief for me, because Guthman in Weighing In describes her class as having triggered her students’ dieting obsessions.) Though several said that they didn’t take snacks at students socials, because it would be too complicated to calculate the calories, which we all laughed about. I used this to highlight the challenge in any human experiment that social scientists call reactivity: the tendency of human participants to change their behaviour in response to being measured or study, usually to best conform with the experimenter’s desired results.

Ah, and if you are curious what the class results were, there were no big surprises: they are college students. Cafeteria food and instant noodles are what they eat, supplemented by the occasional special restaurant meal out with friends.

I encourage all of you teaching a food course to try this Food Diary Experiment with your students. Write to me if you have questions about it, or would like me to forward you materials. And leave comments below if you have any suggestions or ideas about how to improve on it. Thanks in advance!

Pingback: Food and Power, an online course | Comedo Ergo Sum